WASHINGTON, DC, FEBRUARY 1994

As I approached the small auditorium inside the Smithsonian’s Air and Space Museum, I saw my father standing in the doorway cheerfully greeting each of the attendees who had come to hear him speak.

When Dad saw me he gave me a big hug and kiss, and flashed his winning smile. With his radiant brown skin and wavy black hair graying only around his temples, my father was a handsome man.

I didn’t know very much about how he’d become a Weather Officer and Lieutenant Colonel in the U.S. Air Force, but I did know that he was well respected and he delighted in sharing stories about his past experiences.

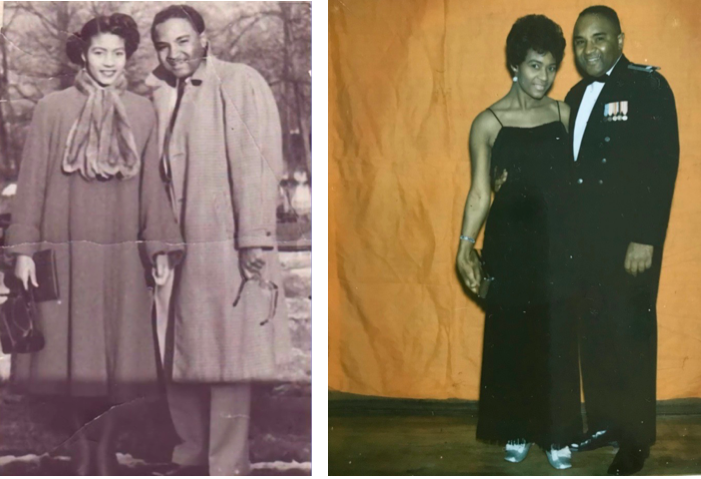

He was wearing that distinctive, red sports jacket — the official uniform of The Tuskegee Airmen organization. He was not one of the original fighter pilots, but the group had expanded its membership to other select African American military men and women because many of the original fliers were aging or had died. They decided this type of open membership was necessary to keep The Tuskegee Airmen legacy alive. Dad lived in the DC area, so he was actively involved with the East Coast chapter of the organization, even serving as President for one term.

Dad had the unique experience of serving in both the Navy and the Air Force, so at almost seventy years old he had quite a story of his own.

To honor Black History Month, the folks at the Smithsonian invited him to speak about the Tuskegee pilots and share his military experience. Since my job was close by, he invited me to attend.

I was in my twenties and I’d grown up hearing stories that he and my mother shared over the years about coming of age in the nation’s capital, the challenges my father faced while serving in the Navy (which was segregated at the time), and the adventures my mom had as a military wife.

That day at the Smithsonian, I was certain Dad was going for shock and awe.

As I settled into my seat and began reading the program, I looked up and spotted my boss (I’ll call him Eric), who had walked into the auditorium. We briefly locked eyes as he scurried towards an open seat on the other side of the room.

He always walked so fast.

I was somewhat caught off guard since I had no idea Eric was coming. Earlier that morning in the office, I’d handed him a flier about the event and asked if I could take an extended lunch to go hear my father speak.

Eric was a tall, slender white gentleman with piercing blue eyes, brown hair, and a mustache that was so thick you couldn’t see his upper lip. As his mustache moved up and down, Eric said it would be okay for me to go and not to worry about rushing back.

He never mentioned wanting to go himself. Maybe he decided to go after I had already left. Or maybe he was just checking to see if I was really where I said I was going to be. In any event, I figured it wasn’t totally weird that Eric showed up since he was a huge history buff. He wasn’t disappointed, either.

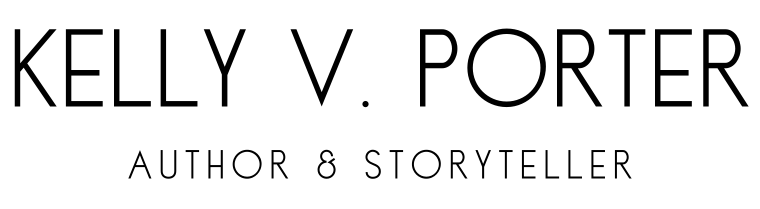

It was 1994 and although Dad had been retired from the Air Force for twenty-four years he was introduced as “Colonel Alonzo Smith.”

Since he retired when I was very young, I don’t ever remember seeing him in a military uniform (other than in pictures), so I always thought it was pretty cool when someone called him “Colonel.”

As part of his presentation, Dad recounted one of his most unforgettable experiences from his time serving in the Navy during World War II.

It was the story of how he and some of his fellow, black sailors were kicked off of a transport ship somewhere along the shores of Indonesia. And in true Lt. Col. Alonzo Smith, Jr. fashion, he put his charisma and public speaking skills on full display.

The audience loved it.

After the program ended, Eric approached Dad. They shared a few words and shook hands before Eric disappeared through the door.

I hung around for a while afterward as Dad answered questions and posed for pictures with a group of schoolchildren. Then I headed back to work. When I got to the office, Eric immediately approached me.

“You should write your father’s book,” said the mustache.

I didn’t think I heard correctly. “He should write his book?” I asked, confused.

“No, you,” Eric said and he quickly walked away.

Why did he always walk so fast?

My first thought was that I didn’t realize Eric had so much faith in my writing skills. I worked in the public information office at a small government agency, writing new material almost daily, but I didn’t consider myself a gifted writer. And an author I was not.

I assumed at some point Dad would tell his own story by writing an autobiography. He’d mentioned it before and had already written down some of his memoirs.

I would leave it up to him.

Fast-forward five years later.

I was now a stay-at-home mom.

One busy day when I was doing something like cleaning up spilled, sticky juice off the kitchen floor, my father called. That was unusual for him because my mother was typically the one to call the house.

“I want you to write my book,” was the first thing he said to me.

Awkward silence…

Wait! Had Eric said something to him that day at the museum? Maybe I should have listened then, back when I had no kids and more time.

“OK…” I said.

Those two letters, OK, became my promise. Still, inside I had mixed feelings.

There was nothing I wouldn’t do for my father, but I had three boys under the age of four. I barely had time to breathe. But I couldn’t refuse.

The next time I saw Dad he gave me a large golden-yellow envelope that contained memoirs about his early years. They were hand-written on lined paper, torn off of a legal-size notepad. Some sheets of paper were tattered and looked like they were decades old.

He’d written down most of his recollections using an inexpensive rollerball pen, the kind that produces saturated black ink. Dad always used those pens even when working out long mathematical equations as he’d done frequently in his career.

I held onto his memoirs but never found the time to read them closely.

“How’s the book coming?” he’d ask every time I saw him.

“It’s coming…” was usually my reply.

Truthfully, it wasn’t really coming at all. There just never seemed to be enough hours in the day to do much of anything, let alone write a book.

I was resentful.

Why was my father asking me to embark on such a big project when, as a busy mother, I had very little time?

What I didn’t realize was that Dad also had very little time.

Less than a year after he requested that I write his book, he died. At seventy-four years young, he was terminally ill with cancer. Ten months after his diagnosis he was gone. I was filled with grief and guilt.

I tucked the envelope of memoirs away in the bottom drawer of my nightstand and there it sat. I just didn’t know how to write his life’s story with so little to go on.

At least that’s what I told myself.

Over the next decade, I raised my kids and pursued a new passion — interior design.

Every once in a while I opened the bottom drawer of my nightstand and caught a glimpse of that golden-yellow envelope peeking out from beneath old greeting cards, photos, and my children’s artwork. Honestly, there probably wasn’t a single day that went by when I didn’t think about the book.

I’d never had the heart to tell Dad I hadn’t started writing his book, and knowing Dad, he never had the heart to tell me he was dying.

Then one day I walked up to my bedroom completely engrossed in self-pity over issues I was having with a client. As I sat on my bed, I looked over at the nightstand, opened the bottom drawer, and pulled out the golden-yellow envelope for the first time in years. I started to read my father’s memoirs and a near-audible thought came to me:

God won’t help you with what you want to do until you do what you’re supposed to do.

I immediately started typing up my own notes based on verbal stories my Dad had shared with me and other family members over the years.

I started researching and I spoke with anyone I could find who knew Dad and was willing to share memories of him. This was a challenge because the folks I needed to interview would be well into their later years if they were still living.

I discovered that many of the people I’d been searching for had passed away. However, I was blessed to find a few of my father’s childhood friends, classmates, and Navy shipmates who were all more than happy to answer my questions. My Uncle George (Dad’s closest brother) also held a wealth of information and sharp memories.

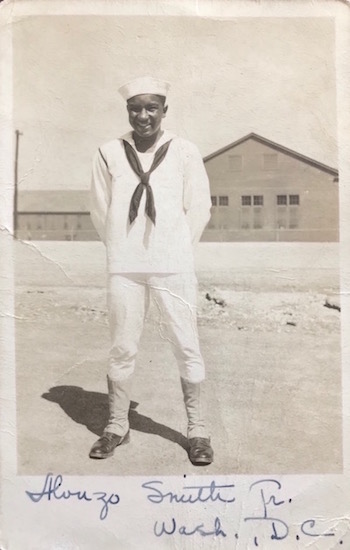

Most importantly, I had my mother. I interviewed her many, many, many times over the past decade. She sometimes grew irritated with my various lines of questioning and my omnipresent tape recorder propped up in front of her face. At times, I’m sure it seemed to her like I was leading an interrogation. Yet, overall she was gracious, open, and honest.

It was because of my mother’s candor and unique perspective that I decided to weave some of her story into the book, which has now become more fascinating than if I had focused on my father alone — not that Dad wasn’t a fascinating man. He was. But now the story is softer, more nuanced, and even wittier.

Yes, only a woman could do that.

I’m so grateful for all of the conversations with my mother because just recently, she passed away at the age of 91. We had a beautiful, close relationship and I was able to document her life the way I should have documented my father’s.

I miss both of my parents every day, but I have comfort in knowing they were deeply spiritual people who loved God. They’re in Heaven with each other. That I know for sure.

What I’ve learned.

Legacy writing and storytelling are extremely important. I cannot emphasize that enough.

Don’t let your family’s amazing stories die with the previous generation. Capturing oral histories from our parents and elders puts us on an incredible journey of discovery and learning. Understanding our family’s stories can inspire us to keep striving towards the goals we set for ourselves.

You don’t have to write a book because truthfully, writing a book is not always enjoyable.

I’ve worked on this project on and off for what seems like forever, constantly pushing back self-imposed deadlines. Writing is hard and the will to keep going can be fleeting. I often wonder if people will even be interested in this narrative. But whether they do or not, I know this story matters, and in completing this book, I’ve kept my promise, that “OK” I gave my father that day. My three sons will be inspired by the story of their incredible grandparents.

I hope you’re inspired by Alonzo and Betty Smith, too.