It practically kills me to admit this, but as a young writer, I was once in the presence of greatness — an award-winning, nationally recognized author. I spent the whole day with her. Yet, I knew close to nothing about her.

Crazy, right?

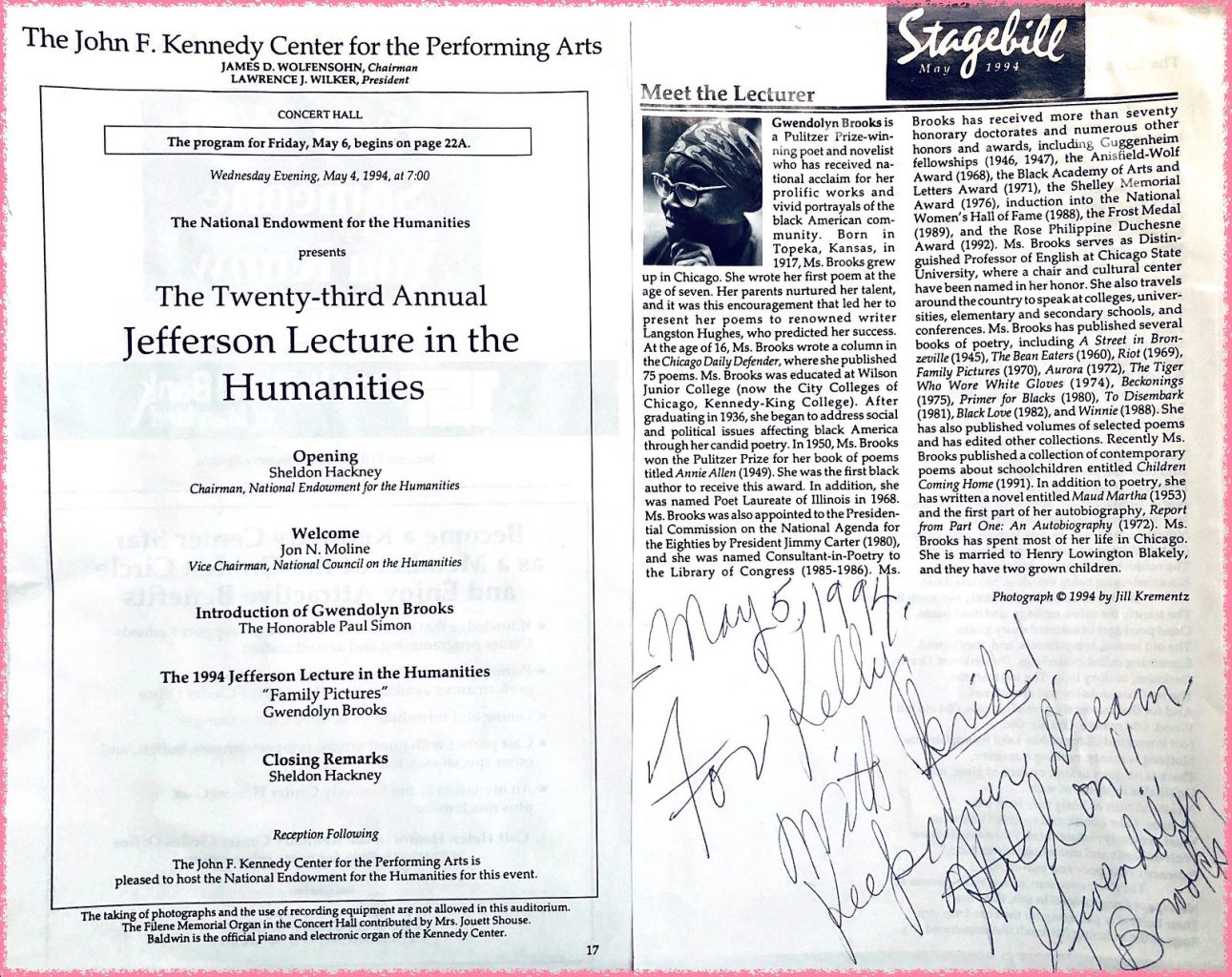

What made it worse was that Gwendolyn Brooks not only had the same cinnamon-hued skin tone as me, but she had the accolades I could’ve only dreamed of having. Ms. Brooks was a Pulitzer Prize-winning poet and novelist. In fact, in 1950 she became the first Black American to win the Pulitzer Prize for her book of poetry, Annie Allen. Among her numerous other honors, she was named Poet Laureate of Illinois and Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress (Poet Laureate of the United States).

I’m not sure whose fault it was that I had little knowledge of Ms. Brooks’ achievements.

I could blame the school system that miseducated me. I grew up in the suburbs of Washington, DC, the seat of civil rights and democracy, yet my teachers offered very few lessons in Black history. Maybe my parents should’ve taught me more about notable Black Americans in history. But, honestly, they were older parents — both born in the 1920s. My history was their real life. And like many Black parents of their generation, they focused on the future, which they hoped would usher in better times for their children.

Or perhaps the blame falls on me. After all, I attended Howard University, “The Mecca,” one of the top HBCUs (Historically Black Colleges and Universities) in the country. Although we didn’t study Ms. Brooks in my Black literature class, I could’ve discovered her on my own if I’d taken the time to read more — like how Ta-Nehisi Coates, a former Howard student, described his self-education in his book, Between the World and Me. He practically lived in Founder’s Library. There were days when I hunkered down in the stacks too, but I only focused on what was necessary to pass my classes. That was a mistake.

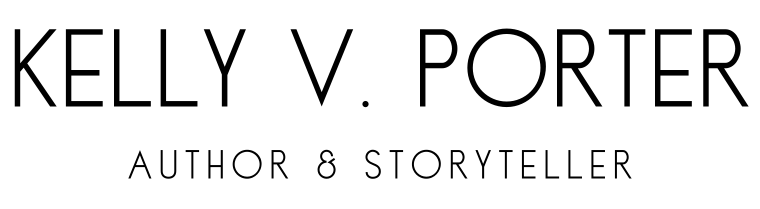

Had I known more about Ms. Brooks, the day I spent with her would’ve been much more rewarding. I was working in communications at the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) in Washington, DC when I encountered her. The agency had selected her to present its annual Jefferson Lecture, an event they describe as “the highest honor the federal government confers for distinguished intellectual achievement in the humanities.”

Blah, blah, blah…

At least that’s how I felt about it at the time. Hey, I was in my twenties, recently married, and living for the weekend. I deemed any kind of lecture as hostile and the way I saw it, Gwendolyn Brooks was just another person with ties to NEH’s advisory council. Little did I know she was a literary icon who was mentored by the likes of Langston Hughes and Richard Wright.

Fortunately, my director, Gary, saw Ms. Brooks’s visit to DC as a golden opportunity for me — the only Black writer in our office. He tasked me with writing her biography. The piece would be published in Stagebill (now Playbill), the official program of The Kennedy Center where the Jefferson Lecture was held. Gary also assigned me as Ms. Brooks’s chaperone for her media-day appearances.

This was huge.

Normally, my immediate supervisor would take on these duties (and yes, he was a little salty). Yet, as Gary later explained, he saw a moment. It was a chance for me, a young Black woman and an aspiring big-time writer to soak up the wisdom of another black woman — an esteemed author, who was seventy-six at the time.

Good looking out because evidently, I didn’t have a clue…smh.

Ms. Brooks had flown in from her hometown of Chicago. From the minute I escorted her from her hotel to the government-issue limousine that would take us around town, I was struck by her confidence, humor, and no-nonsense personality.

With her closely cropped, natural hair, she looked regal. I’m not going to lie. I was nervous. This was the mid-1990s, so I had no cellphone to Google this woman. I had to ask her many of the questions I needed answers to so that I could write her biography. Fortunately, she didn’t seem bothered by that. She was gracious, down to earth, and her warmth put me at ease.

I learned that she wrote her first poem at age seven. By the time she was sixteen, she’d published over seventy poems and then started publishing her work regularly in the Chicago Defender newspaper. She’d go on to publish several books of poetry and a short novel, Maud Martha.

The candid themes Ms. Brooks was known to write about came from her experience growing up in Chicago’s Bronzeville neighborhood and her encounters with racism while attending integrated schools.

“The people in the lobby tried to avoid looking curiously at two shy Negroes wanting desperately not to seem shy. The white women look at the Negro woman in her outfit with which no special fault could be found, but which made them think, somehow, of close rooms, and wee, close lives. They looked at her hair. They were always slightly surprised, but agreeably so, when they did. They supposed it was the hair that had got her that yellowish, good-looking Negro man without a tie.” — Excerpt from Maud Martha, published in 1953 by Gwendolyn Brooks

Ms. Brooks went on to receive a Guggenheim Fellowship and, during the 1960s, she lent her voice to the fight for civil rights. She ultimately started teaching creative writing at several top universities including Columbia University.

At the end of our day together, I was truly enlightened and inspired. However, I realized that if I’d already been familiar with Ms. Brooks’s life I could’ve used more of my time to ask her for advice. Advice on the art of crafting poetry and stories, and how to succeed as a Black woman in the writing business.

I would’ve asked for her advice on all of those things and more had I known I was going to be in the presence of greatness.

It’s been quite a while since my encounter with Ms. Brooks and over twenty years since her death (she died in 2000). I recently came across the biography I wrote about her and as you can see, she autographed it for me. She must have known that I — this clueless young woman — needed her encouragement.

I sometimes wonder what Gwendolyn Brooks could’ve taught me about being a writer. I’ve searched for the answers in her literary works and famous quotes but more importantly, I’ve become a student of history. So much of what we need to understand can be found in the past, in the lives of those who came before us.

Listen, I’m all about living in the present and planning for the future, so I’m not suggesting we dwell aimlessly on bygone eras or the happenings of yesteryear.

Rather, we should look at the past as being a vault filled with valuables — wisdom, lessons, answers, and inspiration for our lives. We just have to be willing to rummage through some things.

I’ve gone back to the research center at Founder’s Library several times since I graduated from Howard, but that’s not necessary for most of us. Just Google stuff (we can do that now). Be intentional. You just may discover something that leads to your own greatness.

“Do not desire to fit in. Desire to oblige yourselves to lead.” — Gwendolyn Brooks