Weather is a funny thing. It affects all of us but do we truly understand how it works? Not sure the White House does, judging by its federal budget proposal for 2026. If Congress passes this extreme budget, one that aims to slash over $163 billion from non-defense programs, millions of Americans will be hurt as essential programs remain in the administration’s crosshairs.

The weather community knows this all too well.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), our nation’s premier weather agency, may not be on the top of the minds of most Americans, but with the summer storm and hurricane seasons approaching, we could soon be feeling the ramifications of the agency’s ill-conceived downsizing. Along with hundreds of employees that were fired and those who chose to resign, we’re left to deal with the sober realization that nature’s fury is no respecter of persons.

Earlier this year, NPR reported that NOAA is to be “broken up . . . keeping the pieces that many Americans are familiar with, like the National Weather Service, and dismantling many of the NOAA’s other offices.”

Familiar with? I ask. What about the “pieces” that are unfamiliar? And is public familiarity a measure for importance?

One of the first emblems I ever remember seeing as a child is the two-toned blue circle that has become synonymous with NOAA. That’s because my father had a twenty-year career at the agency following his retirement as a weather officer in the military (I detail his inspiring life and groundbreaking work in my debut book, The Weather Officer).

Toward the end of his tenure with NOAA, he’d been appointed to the deputy position at what was (and still is) considered an obscure office within the organization—the Office of the Federal Coordinator for Meteorology (OFCM). I’m guessing you’ve never heard of it. And if you have, I just might have to buy you a cup of coffee.

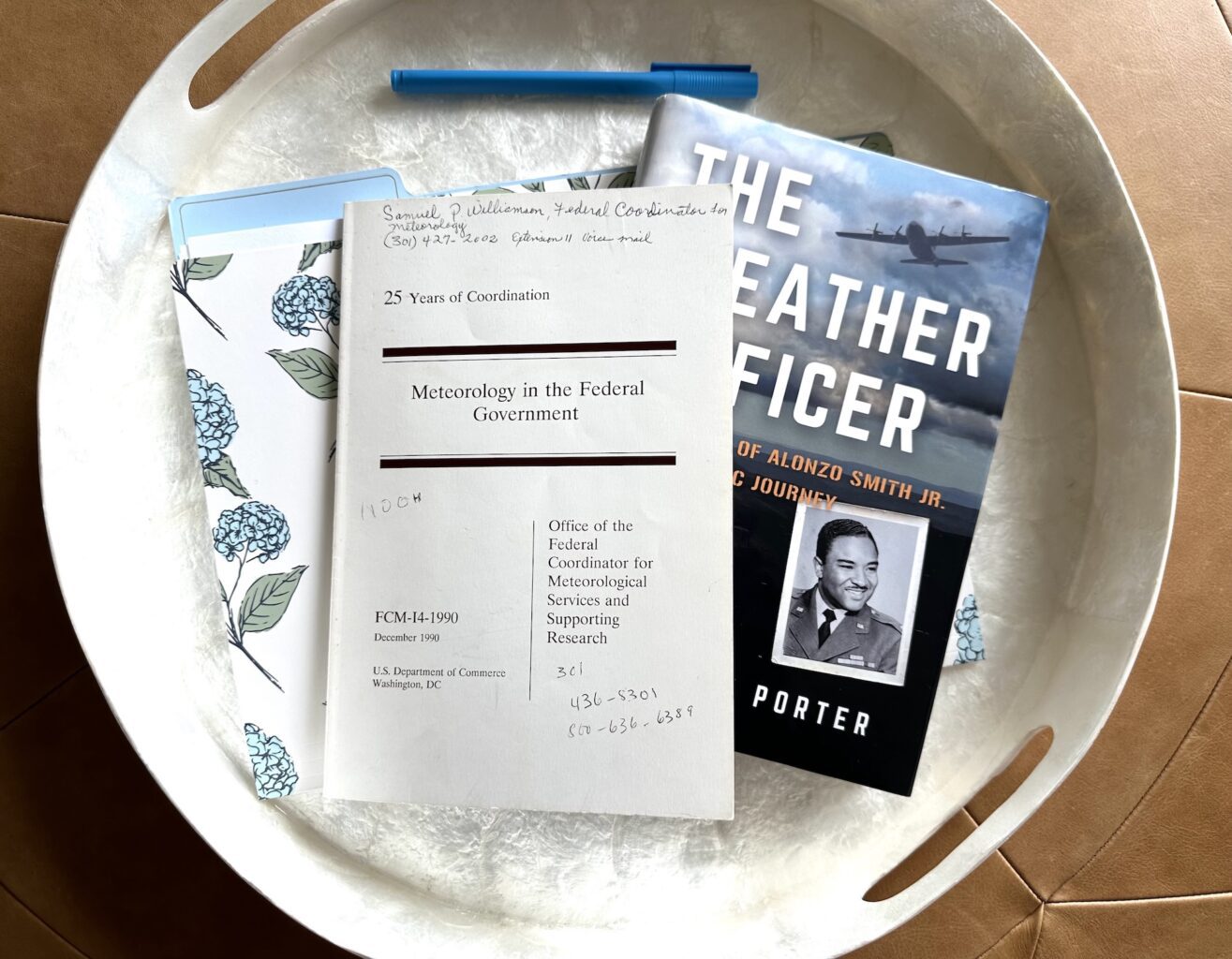

Years ago, I remember having a conversation with a NOAA employee who implied that OFCM was of no value since “no one even knows what they do,” he said to me rolling his eyes. Interestingly enough, after my father died my mom gave me several items related to his career, including a small nondescript booklet, ivory-colored with dark-brown type on the cover.

I didn’t read the booklet right away because after flipping through it, well, I almost fell asleep. Boring AF. It wasn’t until recently that I picked it up again, wanting to understand more about the history of NOAA in light of the current regime’s attempts to dismantle it.

As it turns out, the report was a fascinating compilation of the mission and services provided by OFCM during its first 25 years. It was published in 1990, 4 years after Dad retired from NOAA. From what I understand, agency officials had reached out to him and asked if he would put the report together for their archives. He agreed, although I’m pretty sure they had to coax him off the golf course.

From the first chapter of the report, it’s clear my father held no false notions as to the obscurity of the office in which he’d held a leadership role.

“One of the least known but most influential organizations in the federal government, it is the only government office responsible for promoting the coordination and cooperation among the agencies involved in weather service activities and supporting research,” he wrote.

While we tend to look at weather services as something only provided by weather-focused agencies, the reality is, there are several, critical weather programs that are active throughout the federal government in various departments.

Today, the Interagency Council for Advancing Meteorological Services (ICAMS), the successor to OFCM, oversees the coordination of weather programs at almost 30 agencies, including NASA, FAA, and all branches of the military. Rockets don’t soar, planes can’t fly, and ships won’t sail without timely and accurate weather forecasts. But those are the obvious scenarios.

What about the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), which oversees the National Institutes of Health and Cener for Disease Control? Those agencies rely on weather services, too. HHS uses weather data to issue public health advisories during heat waves and extreme cold, especially as it relates to providing resources to the most vulnerable among us, such as the unhoused population. HHS also uses climate patterns to predict and prevent potential disease outbreaks, like mosquito-borne illnesses.

I also think that sometimes, we take for granted or just don’t pay attention to the many essential ways that collaborative weather services protect us daily:

Nuclear Safety. Nuclear Regulatory Commission uses weather data to monitor cooling systems at power plants, as well as responding to emergencies (I’m old enough to remember the Three-Mile Island Accident).

Environmental Protection. The EPA relies on weather information to monitor air quality and issue alerts.

Agriculture & Forest Management. The USDA depends on weather forecasting for early wildfire detection and firefighting coordination, pest management, and crop protection.

ICAMS also coordinates America’s Doppler radar system, primarily used by the FAA, National Weather Service, and Department of Defense. The same agencies also use a series of lightening detection networks. And of course, there’s our country’s emergency management arm. FEMA works very closely with US weather agencies for evacuation and recovery operations. As our planet continues to warm, we’ll see an increased number of extreme weather events, and FEMA will require even more coordination.

In addition to all of that, ICAMS plays a critical role in the international weather community, due to America’s trusted and reliable voice in the World Meteorological Organization, a global program of the United Nations that includes 193 Member States and Territories. The organization manages the sharing of weather data, climate research, and other under-the-radar things (see what I did there?) like ensuring that the world’s 322 weather satellites floating around in space don’t collide.

I could go on. But the point here is that all of this weather stuff doesn’t just happen. Since 1964, the collaboration and evolution of our country’s atmospheric science machine is one that’s been well-oiled and maintained by NOAA. Unfamiliar pieces. Unnoticed pieces. Take-for-granted pieces. And maybe even boring pieces. Yet, no less critical to our everyday lives.

Unfortunately, as NOAA remains in jeopardy of being broken up, one of the most effective things we can do is keep our collective voice together. We’ve already seen that when the American people are loud enough, we have the power to reverse harmful, misguided policies. But we must be informed, and that is why I write.

Little did I know that I would be helping to amplify the impact of meteorologists and climatologists, and sharing my father’s story at a time when atmospheric science is under attack in unprecedented ways. But, here I am. Not a scientist myself. Rather, a storyteller trying to make a difference by writing about the weather—something that touches all of us.