So, why did I write The Weather Officer? Come with me, back three decades, and allow me to tell you the story of what began on a cold winter afternoon (during my lunch break):

WASHINGTON, DC, FEBRUARY 1994

I approached the small auditorium inside the Smithsonian’s Air and Space Museum on Independence Avenue. That’s when I spotted my gregarious father standing in the doorway cheerfully greeting each of the attendees who’d come to hear him speak.

Dad embraced me with a bear hug and kissed my cheek before flashing his winning smile. With his radiant brown skin and wavy black hair graying only around his temples, my father was a handsome man.

I didn’t know very much about how he’d become a weather officer or a lieutenant colonel in the US Air Force, but I did know he was well respected and he delighted in sharing stories about his experiences.

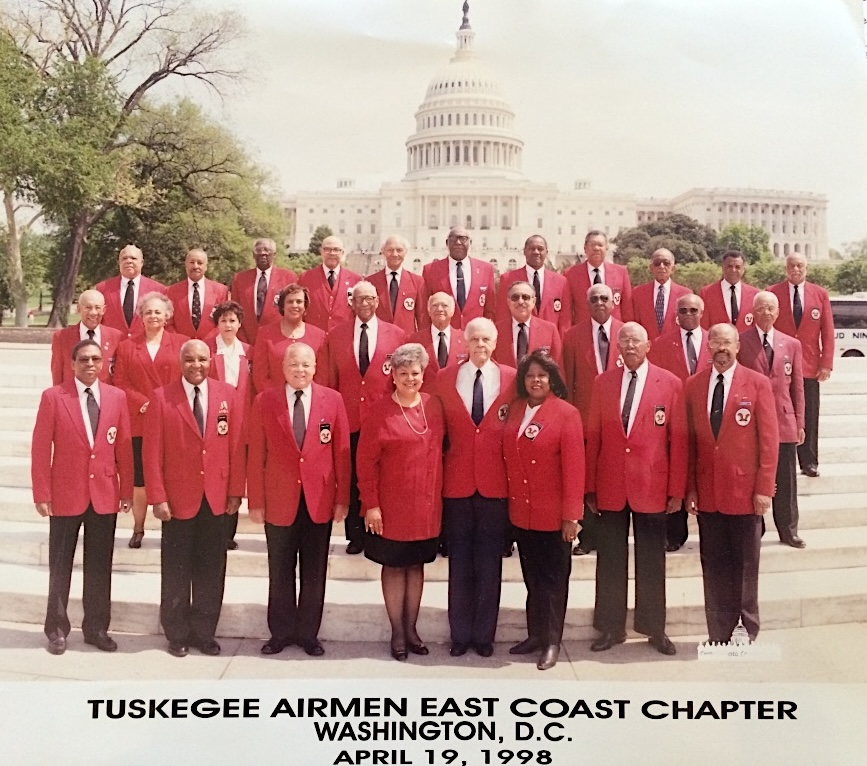

He was wearing that distinctive, red sports jacket — the official uniform of The Tuskegee Airmen, Inc. (TAI), the group of celebrated Black pilots of World War II. Dad had never been a fighter pilot, but the organization had expanded its membership to other select Black servicemen and women because many of the original fliers were aging or had died. They decided this type of open membership was necessary to keep the Tuskegee Airmen’s legacy alive. My father lived in the DC area and was actively involved in the East Coast chapter of the organization, even serving as its president for one term.

Having served in both the Navy and the Air Force, at almost seventy years old, Dad had quite a history of his own. In honor of Black History Month, the folks at the Smithsonian invited him to speak about the Tuskegee pilots and share his own military adventures. Since I worked downtown close to the museum, he encouraged me to attend.

I was in my twenties then, and had grown up listening to Dad talk about his childhood in Harlem, coming of age in DC, and how he was drafted into the Navy during WWII when the military was segregated. Some of his war stories were quite fascinating. That day at the Smithsonian, I was certain he was going for shock and awe.

As I settled into my seat, I spotted my boss (I’ll call him Eric), walking into the auditorium. We briefly locked eyes as he scurried towards an open seat on the other side of the room. He always walked so fast. I was caught off guard because I had no idea Eric was coming. Earlier that morning in the office, I’d handed him a flier about the event and asked if I could take an extended lunch to go hear my father speak.

Eric was a tall, slender White gentleman with piercing blue eyes, brown hair, and a mustache that was so thick you couldn’t see his upper lip. As his mustache moved up and down, Eric said it would be okay for me to go and not to worry about rushing back. He never mentioned his interest in attending himself, so I guess he made that decision after I’d already left. In any event, I figured it wasn’t totally weird that Eric showed up because he was a huge history buff.

Although Dad had been retired from the Air Force for twenty-four years, he was introduced as “Colonel Alonzo Smith.” I always thought it was pretty cool when someone referred to him as “Colonel,” mostly because he retired when I was very young, and I don’t ever remember seeing him in a military uniform, other than in pictures.

During his presentation, Dad recounted one of his most unforgettable experiences while serving in the Navy during WWII in the Pacific Theater, when the military was segregated. He told the crazy story about how the captain of the transport ship he was assigned to kicked him and the other Black sailors off the vessel somewhere along the shores of Indonesia, leaving the sailors there to fend for themselves (the details are in my book).

In telling the story, my father put his charisma and public speaking skills on full display. The audience loved it. After the program ended, Eric approached my father. They exchanged a few words and shook hands before Eric disappeared through the door.

I hung around for a while as Dad answered questions and posed for pictures with a group of schoolchildren. Then I headed back to work. When I got to the office, Eric immediately walked up to me.

“You should write your father’s book,” said the mustache.

I didn’t think I heard correctly.

“He should write his book?” I asked, confused.

“No, you,” Eric said and he quickly walked away.

Why did he always walk so fast?

My first thought was that I didn’t realize Eric had so much faith in my writing skills. I worked in the public information office at a small government agency, writing new material almost daily, but an author I was not. I assumed at some point Dad would write an autobiography. He’d mentioned it before and had already written down some of his memoirs.

I would leave it up to him.

Fast-forward five years later.

I was now a stay-at-home mom, perpetually busy chasing after three young boys. One hectic day, I was doing something like cleaning up spilled, sticky juice off the kitchen floor, when my father called.

“I want you to write my book,” was the first thing he said, after “Hi, it’s Dad.”

Awkward silence…

Where did that come from? My mind raced. Wait a minute. Had Eric said something to him that day at the museum?

“OK . . .” I said finally.

Those spoken two letters became my promise. Privately, I had misgivings. My children were all under the age of four. I barely had time to breathe. At the same time, there was nothing I wouldn’t do for my dad. I couldn’t refuse.

The next time I saw my father he gave me a large golden-yellow envelope stuffed with memoirs about the early part of his life. The passages were handwritten on lined paper, torn from a legal-size notepad. Some sheets of paper were tattered and appeared to be decades old.

He’d written down most of his recollections with a rollerball pen, the kind that produces saturated black ink. Dad always used those pens, even when working out long mathematical equations, as he’d done frequently throughout his career and still did as a math tutor.

I held onto his memoirs but never found the time to read them closely.

“How’s the book coming?” he’d ask every time I saw him.

“It’s coming . . .” was my usual reply.

Truthfully, it wasn’t coming at all. There just never seemed to be enough hours in the day to do much of anything outside of mommy duty, let alone write a book.

I was resentful.

Why was my father asking me to embark on such a big project when I had so little time?

What I didn’t realize was that, Dad also had little time.

Less than a year after he declared me as his biographer, he was gone forever. At seventy-four years young, he’d been terminally ill with cancer and died ten months after his diagnosis. I was devastated. Grief and guilt consumed me. I’d never had the heart to tell Dad I hadn’t started writing his book, and knowing Dad, he never had the heart to tell me he was dying.

I tucked my father’s memoirs away in the bottom drawer of my nightstand and there the envelope lived for years. I just didn’t know how to write his life’s story with so little information to go on.

At least that’s what I told myself.

Over the next decade, I raised my kids and pursued a new passion by starting an interior decorating business. Every once in a while, I opened the bottom drawer of my nightstand and caught a glimpse of that golden-yellow envelope peeking out from beneath old greeting cards, photos, and my children’s artwork.

Honestly, there probably wasn’t a single day that went by when I didn’t think about the book.

One afternoon I walked into my bedroom feeling totally depleted. I no longer enjoyed my work and it just felt as if I was should be doing something else entirely. As I sat on my bed, I looked over at the nightstand, opened the bottom drawer, and pulled out the golden-yellow envelope for the first time in years. I started to read my father’s memoirs and I knew at that moment, I was supposed to be writing that book.

Almost immediately, I started typing up my own notes that captured some of the stories my father had shared over the years. I began my research and spoke with anyone I could find who knew Dad and was willing to share memories of him. This was a challenge since the folks I needed to interview were well up in age, if they were still living at all.

Many of the people I searched for had passed away. However, I was blessed to find a few of my father’s childhood friends, classmates, Navy shipmates, and fellow Air Force officers who were more than happy to answer my questions. My Uncle George (Dad’s closest brother) also held a wealth of information. Uncle George was born in 1926 and he’s still with us.

Most importantly, I had my mother. I interviewed her numerous times over the years, up until she died in 2018 at the age of 91. She sometimes grew irritated with my various lines of questioning and my omnipresent tape recorder that I propped up in front of her face. At times, I’m sure it seemed to her like I was leading an interrogation. Yet, she remained gracious, open, and honest.

I’m so grateful for all of the people who provided information and insight, and helped me to keep my promise to my father.

What I’ve learned.

Legacy writing and storytelling are extremely important, especially now that books are being banned and history is under attack.

Don’t let your family’s amazing stories disappear with the previous generation. Capturing oral histories from our parents and elders puts us on an incredible journey of discovery and learning. Understanding our family’s stories can inspire us to keep striving towards the goals we set for ourselves.

And you know what? You don’t have to write a book. Let me tell you. Writing a book is not easy nor is it always enjoyable.

I’ve worked on this project on and off for what seems like forever, constantly pushing back deadlines when there was more editing and research to be done. Writing is hard work and the will to keep going can be fleeting.

I often wonder if anyone will even be interested in reading my book. But I do know this story matters. By completing this biography, I’ve kept my word. I did what I told my dad I would do. What’s more, I’ve crafted a narrative that my three sons, who are now adults and have little (if any) memory of their amazing grandfather, can turn to for inspiration.

I hope you, too, are inspired by the life and times of Alonzo Smith, Jr., The Weather Officer.